Political (self-)selection and competition

Evidence from U.S. Congressional elections

Who we elect to political office matters a lot. Politicians choose the policies that affect our daily lives, and the socio-economic background of who we elect influences their choices. Electing more women, for example, increases the provision of public goods that are typically favored by women. At the same time, competition in elections has been decreasing steadily. In the 2024 U.S. Congressional election, for example, only 69 out of 435 seats are considered to be at least somewhat competitive (Cook Political Report).

Fewer competitive districts mean that voters have less influence in the choice of their representatives. Additionally, potential candidates may choose not to run in uncompetitive districts.

In this project, I study how competition influences the entry of candidates in the elections for the U.S. Congress. I rely on changes to competition within electoral districts stemming from regular redistricting and estimate a difference-in-differences model with continuous treatment.

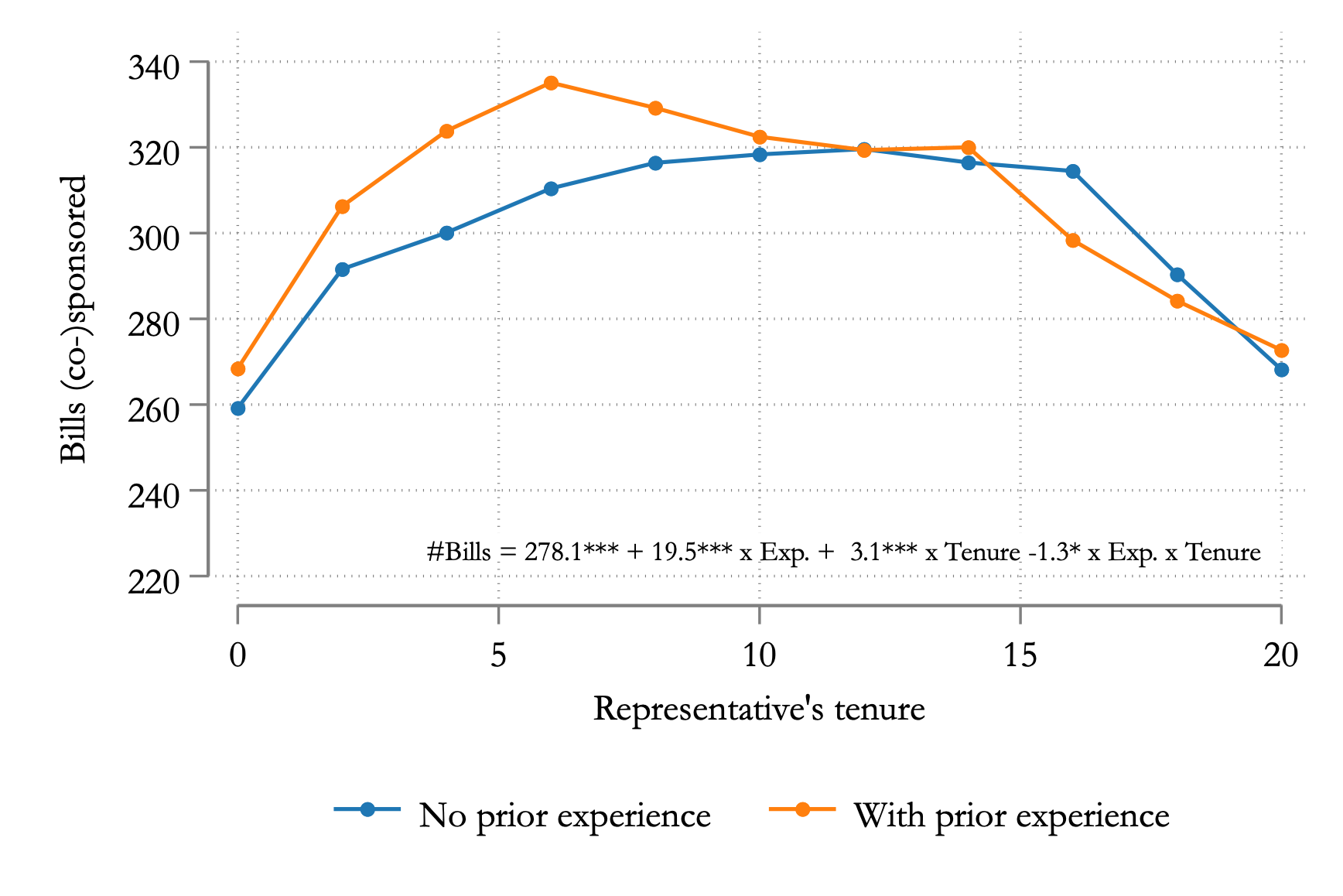

I focus on two candidate characteristics: Previous experience in (local) government and descriptive representation – if the district is a minority district, does the candidate belong to this minority? Both characteristics are important in office. Experience leads to more activity in bill writing, whereas being more descriptively representative comes with less agreement with party lines, potentially in favor of focusing on one’s constituents.

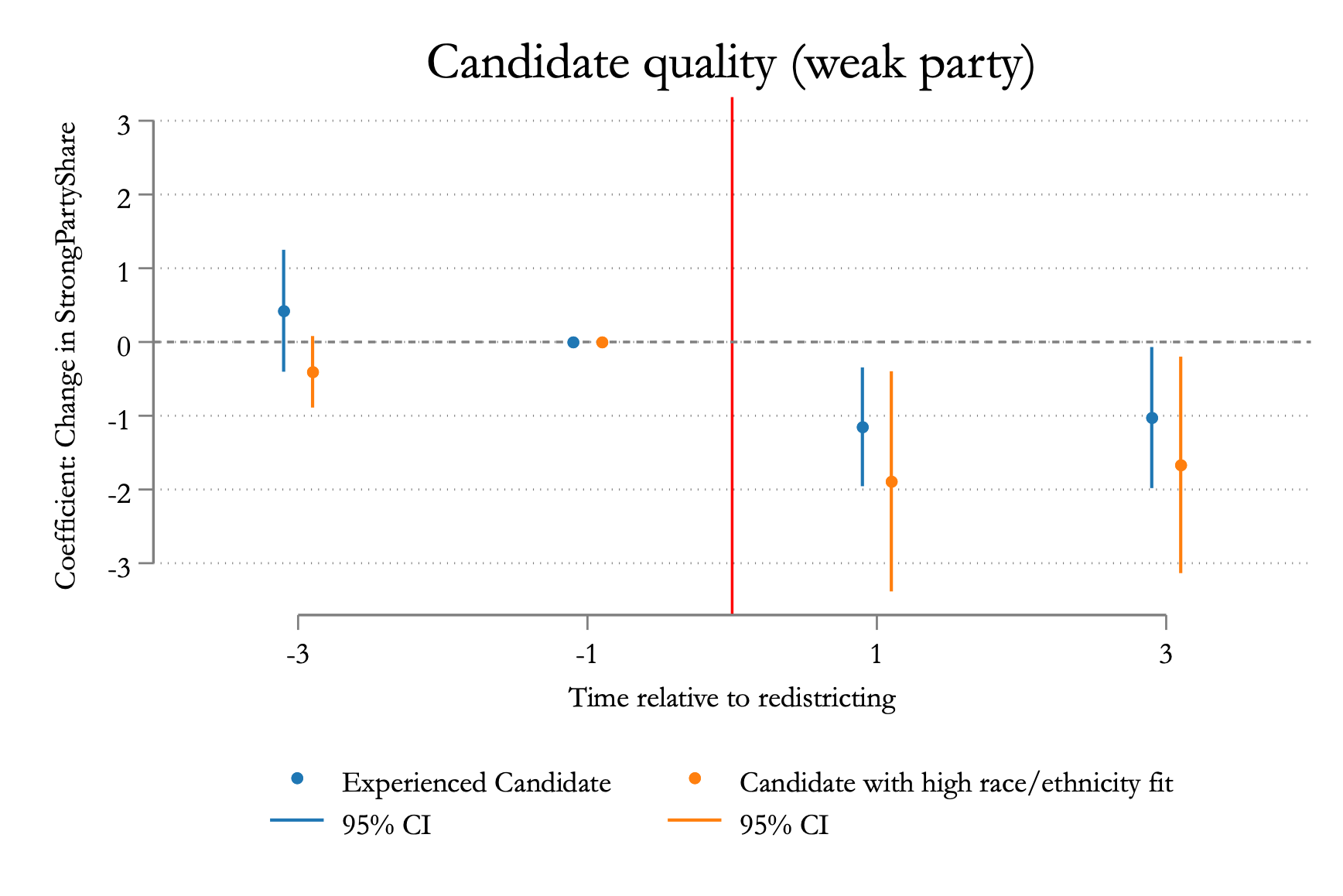

Changes to competition in a two-party system always mean that one party benefits and the other does not. Therefore, I focus on just one of the two, the party that is electorally weak to begin with, the party that has a predicted vote share of below 50%.

The figure shows the coefficient estimates for the average experience of candidates in the primary elections of the weak party. Less competition is always associated with a lower share of experienced, but also a lower share of descriptively represantive candidates.

If decreased competition thus lowers the experience and descriptive representation of candidates in the weak party, does this mean elected officials are worse? No. The effects are roughly opposite in the strong party, which means that lower competition in the general election increases entry of high-quality candidates in the primary election of the strong party sufficiently to make up for the lower quality of candidates in the weak party.

In the paper, I also study the mechanism behind these entry patterns and show that potential candidates most likely respond to preferences of party members and donors, a result that is in line with the notion that competition shifts from the general election to a smaller set of voters – party members and donors.